All coaching is not the same. I know this because I tried to make it all the same and fell flat on my face. When I first began working with executive leaders one-on-one, I had an assembly line approach to the process and found it to be extremely ineffective.

Then I wised up.

One of the biggest ways executive coaching differs from one individual to the other is the kind of leader you’re coaching. Not just in personality and learning style, but in the experience level of the leader. Over the years, I’ve come to see that this is the most important filter to apply to the practice of coaching.

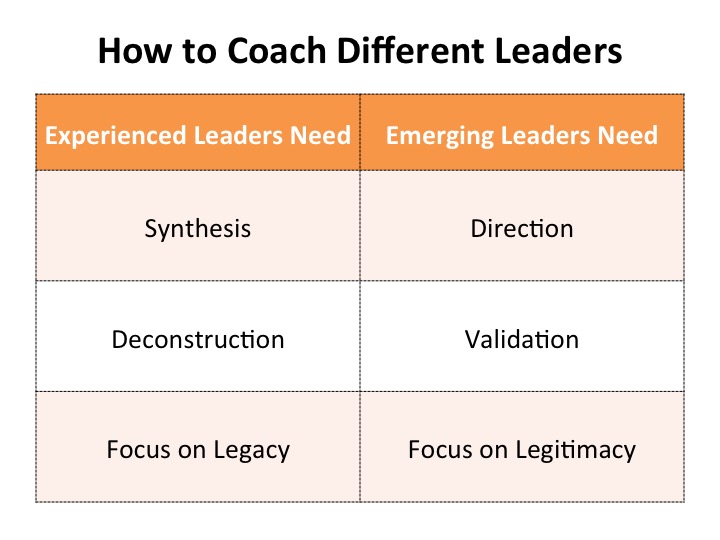

Whether you coach formally for your firm or coach leaders who come to you informally, there are three big differences between the way you should interact with an experienced leader and the way you should interact with an emerging leader. They are:

1. Synthesis versus Direction

2. Deconstruction versus Validation

3. Legacy versus Legitimacy

1. Synthesis versus Direction

One of the things that characterizes new leaders is this: They don’t know what they don’t know. Often as you coach them, they’re genuinely stuck, with no idea of what to do next. Here’s where direction is perfectly appropriate and received by an emerging leader as water to a parched soul.

It’s just the opposite, however, with an experienced leader.

I’ve found that an experienced leader needs to talk through all the issues at hand. They need to get everything out of their head, laying all their cards on the table (insert your favorite metaphor here). Then they need someone to summarize for them what they just said. Not a rote word-for-word summary, but summary with insight. Or what I call synthesis.

I had an interaction like this with one of the CEO’s I’m working with right now. For the better part of an hour she laid out the details of a challenging and emotionally charged situation that she faced. Listening intently and asking thoughtful questions, I summarized the steps forward in a sentence or two, using her own words in the summary. In response she exclaimed, “That’s exactly it!”

This woman was bright, passionate, and uber-experienced in her field. But she was way too close to the problem to see the solution. The job of a coach with leaders like this is to sit outside of the situation and frame it for them, synthesizing what they need to do in their own words.

2. Deconstruction versus Validation

Sometimes, however, synthesis is not enough. Sometimes leaders are tripping all over themselves, tangled up in their well-worn ways of doing things. This is where deconstruction comes in. Deconstruction helps experienced leaders reexamine how they work and decide if the way they’ve always done something is really the way they should do it now.

Deconstruction is tricky, however, because no one wants the comfortable walls of their house torn down around them. So do it with grace. But do it you must, for often it’s the only way to build a bigger, better house. Remember the seven last words of a dying organization: We’ve never done it that way before.

Emerging leaders rarely need deconstruction, because much of their leadership house has not yet been built. And if you do deconstruct it, you may unhinge them completely. What emerging leaders need is validation that they are doing the right thing, and validation that, if they persevere, good will come. They are, in a sense, on the field of play looking up to you in the stands for approval. When you give it to them, you also give them the confidence to move forward without fear.

When Do You Provide Which?

And, of course, when to provide synthesis and when to provide deconstruction is the great art of coaching experienced leaders. For that matter, too, when to provide direction and when to provide validation.

As an art and not a science, you learn this more by feel than by formula. Knowing that all coaching, and all coaching clients, are not the same is the start to mastering this art. But the real secret is developing a finely tuned sense of when to lean in and when to back off, and then having the courage—or the self-restraint—to do either.

The guiding question I ask myself in these moments is: What’s in the best interest of this leader? As opposed to what might be the most comfortable to me in the moment, for often they are not the same.

3. Legacy versus Legitimacy

The final way coaching experienced leaders and coaching emerging leaders differs has to do with where they are on their leadership path. At the beginning of a person’s leadership journey, they need help gaining legitimacy. They need to be encouraged to embrace the kinds of challenges that allow them to prove themselves and be seen within the organization as the go-to person to get stuff done.

Once leaders have achieved legitimacy, however, they can lose their way. That is, when no challenge remains, they may coast. That’s why discussions regarding legacy are so important. Legitimacy precedes legacy, for no leader who’s not respected by his or her peers and direct reports can leave a legacy. But this shift in thinking is critical, from making one’s way in leadership to leaving a mark that’s hard to erase.

For leaders who are younger, the word legacy may not connect well because it conjures images of old age and retirement. When working with a younger leader, I’ll use the phrase “leadership brand” and ask, “What do you want people to think of when they think of you as a leader?” When a younger leader answers this question, they do, in fact, begin leaving a legacy.

Whether you use the word legacy or brand, the point is this: Those who are no longer new to leadership need to be challenged differently to be their very best. The way in which you do that is by appealing to their inherent human desire to make a difference in the world and change the lives of people in the process.