Change or die.

That’s what the bumper sticker said on the car in front of me.

As stark as that statement may seem, it’s been my experience from over a decade of working with organizations both large and small, the latter is preferred over the former.

Not that anyone would it admit it. No respectable leader would announce to the world, “I would rather die than change.” But they say it nevertheless.

They say it with their actions. Actions that fail to foster the climate in which change flourishes. And they say it with their inaction, failing to deal with forces that resist change.

I’ve identified four deadly decisions that kill change and offer answers to them as a path forward to better. They are:

- Deny reality

- Move too fast

- Manage change, not lead it

- Avoid–or attack–opposition

Deadly Decision One: Deny Reality

Dysfunctional families and dysfunctional companies have the same fatal flaw: a strict code of silence that rules their relationships. This code of silence prevents people from speaking the truth, speaking it openly and speaking it honestly.

As a result, these human institutions live in a perpetual state of denied reality. For a business, denial like this can be devastating.

Marketshare is eroding, but no one will talk about it. Customers are unhappy, but no one will listen to them. Cash is in short supply, but the downturn is blamed on the economy (the government, the president, the competition, insert your own reason here).

Human beings have an amazing capacity to ignore the obvious until it’s too late. And so it is with change, killed at the very start, nipped in the bud before a bloom ever begins.

You can avoid this mistake, however, by becoming a leader who accepts feedback. Not just accepting it, though, but actively seeking it out.

You can become a champion for change by learning how to listen, really listen, to the people around you, even (especially?) when what they have to say cuts against the grain of the status quo, and, perhaps, your own personal comfort.

In other words, stop denying reality and break the code of silence that exists in your company (By the way: your family will thank you for this, too).

Deadly Decision Two: Move Too Fast

The second mistake that kills change looks likes a Seinfeld episode. You know, the one where they’re traveling upstate and George is driving so fast that Jerry can’t keep up with him. George has the directions to where they’re going and wants to make good time, but Jerry can’t see his car anymore and ultimately gets lost.

Like most Seinfeld episodes, we’re amused by the crew getting mad at each other and the hilarity that ensues from their self-inflicted frustrations.

In the real world, we’re not amused, and the frustration of leaders moving too fast don’t produce hilarious outcomes. They kill change.

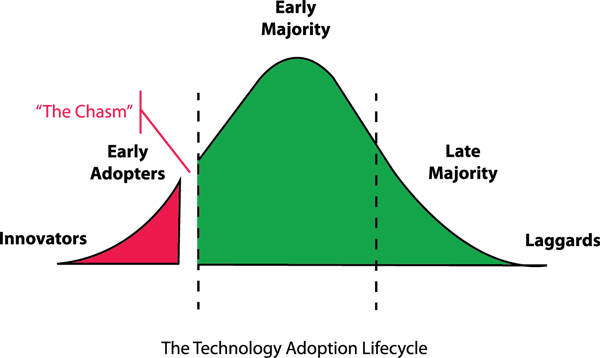

Geoffrey Moore in his seminal work, Crossing the Chasm, reveals the way people embrace change in the technology adoption bell curve.

On the left of the curve is early acceptance of change by Innovators and Early Adopters. In the middle of the curve is mainstream acceptance of change by the Early Majority, and on the right of the curve is late acceptance of change (or no acceptance at all) by the Late Majority and so-called Laggards.

The chasm that exists between Early Adopters and the Early Majority drops off into what Mr. Moore calls “the valley of doom,” or where change goes to die.

This death occurs because Innovators initiating change, sometimes securing expensive financing for it, misinterpret the enthusiasm of Early Adopters and assume the rest of the world will be just as enthused. They are not—at least not at first—so a new technology falls to its death in the Valley of Doom, never to rise again.

Change leaders do the same when they assume the majority in the middle will be just as excited about the changes they’re proposing as Early Adopters. And, again, they’re not, not at first anyway. But leaders keep pressing ahead, driving faster and faster and faster (like George Costanza), leaving their people lost and frustrated.

The truth of the matter is this: change takes time. And because it takes time, leaders must not move too fast with it.

This means taking the time to engage the middle, to explain the reasons for change, to paint a compelling picture of the future when change has been fully implemented, and to answer the dozens and dozens of questions that arise when they do.

For it’s acceptance by the middle, not Early Adopters, that’s key to the success of any change initiative.

This is true for two reasons. First, the middle is where the majority of people exist and critical mass in favor of change can’t be gained without them. That’s a raw statical reality. The second reason is people in the Early Majority are the ones best positioned to win over the Late Majority and the Laggards, making change an overwhelming mandate in your organization and not just a passing fad.

Deadly Decision Three: Manage Change, not Lead It

Google the word change and you’ll find another word closely associated with it, management. As in “change management.” The problem is, change management doesn’t work. You must lead change, not manage it.

It’s not my intent here to perpetuate the silly debate that rages on the Internet about which is better: being a leader or being a manager.

Anyone working with a leader who pays no attention to management whatsoever suffers the painful consequences of missed meetings, unanswered email, dropped details, and wasted resources. Direct reports who have a boss like this beg them to acquire these missing skills.

And, yes, the other side of the coin is painful too, cautious analytics who seem to be afraid of their own shadow and fail to take the business in new directions.

The truth is, we must both lead and manage. But in that order. The cart doesn’t come before the horse. The horse comes first and drives the cart down the road. Neither does the horse run wildly through the countryside, however, but delivers its load while pulling the cart.

Here’s how to do this when it comes to change:

- First, leading change requires us to create a sense of urgency around the completely unacceptable nature of current unreality, and then to paint a compelling picture of future. In short, a champion of change knows how to cast vision, and vision is a coin with two sides: rejection of the status quo and passion for a new reality.

- Second, leading change requires more than just words, even very persuasive words. The most persuasive thing a leader can do is act. Champions of change don’t have a double standard for the future they’re proposing but lead by example, acting with full integrity to it. They also insist, without compromise, that the leaders who work with them do the same.

- Third, leading change requires us to understand the implications of change. That is, to foresee the unintended consequences that will occur when it arrives and to carefully prepare for them. This is management at its best, planning for contingencies and being ready to respond to them.

More than once I’ve seen dropped details derail a perfectly good, and desperately needed, change initiative. A lack of attention to important details can bring a grinding halt to future progress and erode any trust you’ve established that the future will be better than the present.

Finally, please observe the ratio of leadership and management I’m proposing in the paragraphs above: 2:1. That is, two parts leadership, casting vision and leading by example, and one part management, attending to important details. In my opinion, this is the mix that works best for successful change initiatives.

Deadly Decision Four: Avoid—or Attack—Opposition

Sir Isaac Newton was right. Remember him? Science … freshman year … high school. Yeah, I know it was a long time ago. A very long time ago.

Newton’s second law of motion states this: every action has an equal and opposite reaction. True for the physical world, and for the corporate one.

Every change initiative—and I mean every one, without exception—will have forces that resist it. If there weren’t forces that resisted it, change would not be necessary for it would have been achieved already. This is a simple, logical conclusion.

Those forces are the “opposite reaction” to your action, and will be “equal” to your energy in their resistance.

Leaders take two dramatically different approaches to the opposition to change, or alternate between them. Neither works.

Some leaders completely avoid opposition to change, leaving critical issues unaddressed. They do this, naively thinking that the opposition will decide one day to quietly fade into the fabric of the furniture. They won’t, maintaining their opposition as change dies a slow and painful death.

Other leaders do the alternative. They attack their opposition mercilessly, naively thinking that they’ll cave under a barrage of mortar fire. They won’t either. What actually happens is this: public and private attacks strengthen the opposition and harden their resolve to resist change at all costs. Cold. Dead. Hands.

Those who oppose change must not be avoided or attacked, they must be engaged. We must come to them with an honest heart and an open hand to collaborate in making change work. In most cases—not every case, but most of them—when I’ve done this, those who initially opposed me have become my most loyal supporters.

This takes time, but change takes time (See: Deadly Decision Two), and the investment is worth every minute.

Here’s the Bottom Line

People have many fears, rational and irrational.

There’s the fear of death, second only to the fear of public speaking. There’s also the fear of spiders, the fear of germs, and the fear of angry white male presidential candidates (who are, strangely, a lot like spiders and germs).

We needn’t fear change, however. It can be the best thing to happen to us and the organizations we serve. Change brings growth and change brings opportunity, if we let it.

If we approach it with our eyes wide open to reality, taking the time needed for it flourish, leading it and managing it (in that order), and courageously collaborating with those who oppose it.

In other words, there’s no need to die. Change.